“Lust for comfort

Suffocates the soul

Relentless restlessness

Liberates me”

Bjork, Wanderlust

Inside the rusted remnants of 142 bus, abandoned in the ice of Alaska a few kilometers from the town of Healy, the young Christopher McCandless spent the last three months of his life exclusively feeding on berries and small animals; almost completely exposed to the winter cold, malnourished and too weak to seek help, Christopher died twenty-four years after he had left behind the prospects of a lifestyle that was too ordinary for him, as he was eager to pack a backpack and begin its journey into the wild.

His story, made famous by the book Into the Wild and the subsequent film adaptation, shows us clearly how the unknown represents a call that some can hardly resist. But what can push a person to leave the safety of civilization, and in some cases the certainty of a stable future, just to satisfy their thirst for adventure? Can the incessant need to travel and to make more and different experiences turn into a real disease, where such needs become abnormal and push people to systematically repudiate their daily life?

Just like Christopher McCandless, some people feel this innate impulse constantly; it’s the shape that changes (it is determined by one’s possibilities) but not the content: the irresistible desire to explore, in its most extreme manifestation, could be justified by Wanderlust syndrome.

Despite being quite English-sounding, the word Wanderlust comes from the union of German words Wander (roaming) and Lust (obsession). As you can easily guess, the Wanderlust syndrome identifies the desire and willingness to constantly undertake trips, often to unconventional destinations; people who suffer from this particular syndrome spend a lot of time planning departures, compulsively consulting websites looking for good offers, and talking assiduously about the places they have visited or would like to visit in the near future.

For sufferers of Wanderlust syndrome, the journey becomes a real catharsis (whatever the destination might be), while the daily routine, with its recurring landscapes and repetitive tasks, is a narrow prison from which to escape. With an attitude that is very reminiscent of the ancient explorers of the past, travel-addicted people dream journeys to unknown lands, far from the ordinariness and bustle of the metropolis to which they are accustomed.

However, there is no official classification of this disorder at the moment. From a strictly clinical point of view, it would not be correct to speak of a Wanderlust syndrome diagnosis, nor we could consider those who often feel the need to travel worthy of medical attention who so.

Yet, some people seem to experience particular anxiety if they are forced to drop their anchor and stay in a certain place for too long; leaving becomes a spasmodic need, an urgency to which they can not and do not want to avoid. How come is possible that some of us become so obsessed with the unexplored that is makes every day life an unbearable burden, while others find themselves perfectly at ease in the places where they were born and have always lived?

Surprisingly, the answer could be enclosed within our genome. A 1999 study, headed by Professor Chuansheng Chen of the University of California, have identified a gene variant which can encode a transcript of the dopamine D4 receptor (in its mutated form defined as DRD4-7r) able to justify the relentless need to explore.

By processing the data obtained from a sample of individuals from 39 different populations, and comparing the presence or absence of the mutated gene with migratory patterns of the subjects’ population, Cheng was able to prove the existence of a positive correlation between the distance traveled by the population and the presence or absence of the mutation; in other words, those who had the gene variant for the D4 receptor belonged to a population that, during its evolutionary history, was found to cover greater distances. On the contrary, people who belonged to sedentary populations had not been able to develop the mutated variant, according to the results.

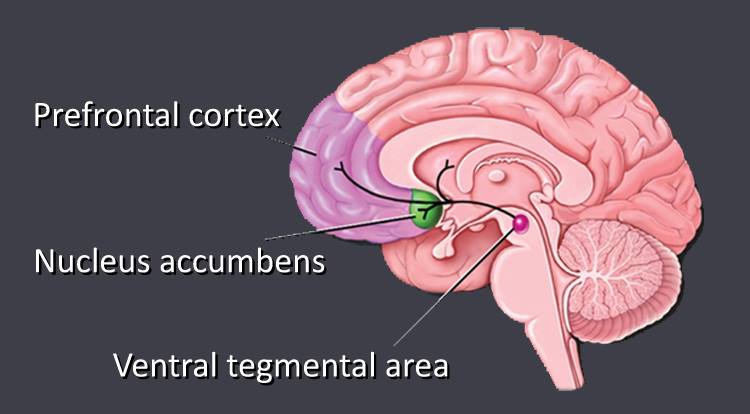

Specifically, the DRD4-7r variant seems to encode a different structure of the dopamine D4 receptor, a type of receptor present in large concentrations along the mesolimbic pathway. This fundamental brain pathway, which ranges from the ventral tegmental area to the Nucleus accumbens, contributes to form a special system called “the reward circuit”, in which dopamine is the main neurotransmitter: this circuit is composed of a set of synaptic connections that are activated whenever a motivational stimulation (food, warmth, sex) is given; this encourages certain behaviors and facilitates their repetition; from an evolutionary point of view, the neurophysiological system directs us towards the pleasant stimuli, guaranteeing survival and favoring the preservation of the species.

The reward circuit is also involved in the development of addiction to narcotics (we talk about it here), such as cocaine, heroin and alcohol; the intake of these substances, followed by devastating neurophysiological imbalances, overlaps with the search of food, the need for sleep, the need for a partner. The neurochemical equilibrium alteration brings those suffering from addiction to leave out any other stimulation in favor of the one resulting from the drug intake; this helps to develop and exacerbate tolerance of the substance itself (so that, for an increase in the frequency and quantity of drug intake, there is a decrease of the desired effects, forcing the dependent person to assume ever more drugs).

One of the hypotheses developed after Chen’s study is that, in those people who have the mutation DRD4-7r, travelling could directly activate the reward circuitry, and thus play the role of a positive reinforcement, like any substance capable of creating addiction; similarly, the impossibility to go on a journey for a long time, understood as the absence of positive stimulation, could justify the daily anxiety that accompanies the routine of those who are supposedly affected by Wanderlust syndrome.

However, Kenneth Kidd, a member of the team identified the DRD4-7r variant and now a professor at Yale University, suggests caution: according to him, the mutation of a single gene is not enough to cause such a big difference in behavior; indeed, it is likely that the tendency to develop Wanderlust is at least the result of the combined action of multiple genes, which are capable of promoting not only the motivation necessary to the movement, but also the physical and physiological means necessary to that distinctive lifestyle.

Anyway, it seems that the involvement of dopamine and of the reward circuit is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition in determining the typical Wanderlust restlessness. Some authors, in spite of Chen studies, tend to downplay the role of DRD4-7r single mutation in favor of a series of elements rooted in the course of child development: in conjunction with the variation of the D4 receptor, these elements may explain why some of us are so prone to travelling.

According to Alison Gopnik, psychologist and also professor of child development at the University of California, the propensity to exploration could come from a massive development of our imaginative capacities. Human beings, in fact, enjoy a unique status in the entire animal world: we live a very long childhood, in which we can continue to enjoy the protection of our parents and also indulge in our desire to explore in complete safety.

Even children’s games could play a key role in the development of Wanderlust syndrome: lots of animals play during infancy, but they generally do that to practice skills such as hunting and fighting, which are activities that will become fundamental for their survival. Human children, on the contrary, play by designing hypothetical scenarios and questioning the hypotheses through a series of trial and error: they are able to take in hand their mother’s ladle and turn it into a spaceship, and then wonder how fast it could go once launched towards the wall. They can also wonder, for example, if tilting their arm upward could make the ship can reach a greater height, or land even further compared to the previous launch.

According to Gopnik, this tendency to experiment, if maintained during adolescence and adulthood, could represent one of the fundamental characteristics of the explorers of the past and, today, of those people who can be considered affected by Wanderlust syndrome. Given the results of these studies, we could consider the tendency to travel the result of atavistic, innate mechanisms, governed by very specific neurochemical changes, but at the risk of neglecting the elements that best define our humanity and that, on the contrary, can hardly be defined with precision. Fifty years ago, we started our journey to the most remote areas of this planet and even today, after exploring the farthest corners, we seem determined not to stop. We crossed the deepest oceans and climbed the highest mountains and now, looking up at the stars, we are going the biggest challenge of our history as explorers.

Perhaps, it is good to end with the most beautiful and difficult question we can ask ourselves about it: here are the words of Svante Pääbo, director of Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics: «We jump borders. We push into new territory even when we have resources where we are. Other animals don’t do this. Other humans either. Neanderthals were around hundreds of thousands of years, but they never spread around the world. In just 50,000 years we covered everything. There’s a kind of madness to it. Sailing out into the ocean, you have no idea what’s on the other side. And now we go to Mars. We never stop. Why?».

Graduated in Psychological sciences and techniques at Firenze University

Info, contacts and articles here

Bibliography

Chen, C., Burton, M., Greenberger, E., & Dmitrieva, J. (1999). Population migration and the variation of dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) allele frequencies around the globe. Evolution and Human Behavior, 20(5), 309-324.

Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A. N., & Kuhl, P. K. (2009). The scientist in the crib: Minds, brains, and how children learn. HarperCollins

Krakauer, J. (2009). Into the wild. Anchor.

Lichter, J. B., Barr, C. L., Kennedy, J. L., Van Tol, H. H., Kidd, K. K., & Livak, K. J. (1993). A hypervariable segment in the human dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) gene. Human Molecular Genetics, 2(6), 767-773.